Back in 1979, I was just starting out as a government contract negotiator

with the Navy Department in DC. They had hired a large number of us recent

college graduates, a bunch of 20-something idiots who thought we owned the

world.

One of our favorite pastimes, I hate to admit, was making fun of the career

bureaucrats in the office who were nearing retirement. One guy, who had been a

Helldiver pilot off the

Ticonderoga during the invasion of the Philippines,

spent every day bombastically retelling his story of being shot down, to the

point where we could all recite it over drinks after work. Another guy, long

past retirement age, took his role as floor warden so seriously that he had

stopped doing any official work and spent the day wandering around in his yellow

hardhat, passing out copies of his 300-page manuscript calling for a world

government run by - you guessed it - himself. Yet another guy, who looked like

an old, skinny, even weirder version of Clint Howard, impressed us all with his

dedication and his long work hours - until we discovered that he was, in fact,

living in the office. They were all deep mines of amusement to us.

But the one we made fun of the most was a guy named Stan Casanove. Stan was

a little guy, just over five feet tall. He had a moon-shaped face and a body

shaped like a pear. He wore thick bottle-bottom glasses, had large unwieldy

hearing aids in both ears, and he walked with two aluminum canes. He almost

never talked, and we assumed he was just slow. Some of us got pretty good at

imitating his whispery voice, his halting walk, his way of looking around

without moving his neck. We thought he was hilarious, and he became even more

laughable when, during a fire drill, he pitched face-first down a concrete

stairway (just missing me) and ended up with grotesque stitches across his

face.

Soon afterwards, Stan retired, and we all ponied up a couple of bucks and

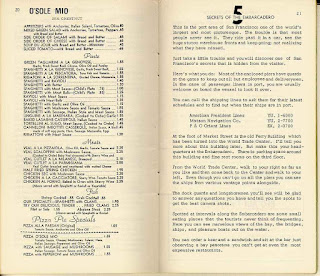

took him to the Orleans House in Rosslyn, one of the few decent restaurants in

Northern Virginia back then, famous for its 100-foot salad bar. After we ate,

the boss made a little speech (which showed us he didn't know Stan any better

than we did), and Stan got up to say thanks.

"I know some of you make fun of me," he started. "You say

things behind my back. But none of you know anything about me. You never

bothered to ask about my canes, my hearing aids, my glasses. You never bothered

to talk to me at all."

"Well, let me tell you something about myself. I served in the Army in

the war. I was stationed on Corregidor. And I was captured by the Japanese when

Corregidor fell."

Dead silence in the restaurant.

"They marched us 60 miles, and a third of us died on the way. No food,

no water, and if you collapsed, they chopped off your head with a samurai

sword. I survived the Bataan Death March - and I survived three years in a POW

camp. Not many of us did.

"My glasses?" He waved at his thick spectacles. "One guard

took great pleasure in hitting me upside the head with a wooden plank until I

was blind.

" My hearing aids?" He gestured at them. "A guard didn't

think I was listening to him closely enough, so he punctured both my eardrums

with a stiletto.

"And my legs?" Nodding at his canes, "I didn't leap up fast

enough when the camp commander came to our barracks, so the guards broke both

my legs with a lead pipe and refused to set them.

"But these are just things that happened. They didn't diminish me, or

make me any less a person in the eyes of God. I'm proud of my service to the

country, and the work I have done here at Navy as a civilian. I hope that you

find as much fulfillment in your career as I have. Thank you." And he sat

down.

I have never, before or since, felt as mortified, as embarrassed or as

humiliated as I did at that moment. I glanced at my officemates. The guys were

beet-red, and some of the girls had tears running down their cheeks. Even the

old guys looked stunned.

I grew up as a very sheltered kid, went from a quiet childhood to a good

high school to an excellent college to a good job. But I had never been

confronted by real life like that. I'd never had my immaturity, my cruelty and

my heartlessness thrown in my face like that. I'd like to think it made me a

better person. And I hope my compatriots, all nearing 60 now, took the same

thing from that experience that I did.

Rest in peace, Stan. And I'm sorry.